My dad insists he’d been taking me there since before I could walk, but my memory only goes as far back as 1994—the summer Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, Major League Baseball went on strike, and my parents were still married, if only on paper.

My sister, Hannah, and I were living with my mom at the time, in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn. Hannah was five and I was seven, and every other weekend we would walk across the crooked highway overpass to visit my dad in Red Hook, two miles away. But the first time I remember going to Henry’s End, my dad picked us up. From the front seat of his tomato-red Chevy Astro, he cursed as he strained to find parking on the narrow cobblestone streets—streets that, he told us, used to serve as thoroughfares for horse-drawn carriages.

“You won’t believe this either,” he said, “but I used to come here all the time with your mom.”

Henry’s End was located—as the name suggests—where Henry Street dead-ends into Fulton, on a quiet commercial strip a few blocks from the on-ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge. Like the railroad-flat apartment where I grew up, the restaurant was crowded and narrow. A row of slate-topped tables stretched from the foyer to the two bay windows that framed the view of the fire escape. Ceiling fans whirred softly beneath a tapestry of checkerboard tiles. It was the kind of place you went for special occasions—birthdays, anniversaries, engagement dinners—a restaurant that, for my dad, could just as easily impress his children as it could his new girlfriend.

*

When my sister and I were growing up, being biracial was still a spectacle. The only thing more taboo for my Chinese mom than marrying outside her race was getting a divorce. She instilled in us early that, in the conservative Italian neighborhood where we lived, having two sets of parents needed to be a secret guarded with as much vigilance as the country our grandparents had emigrated from. Still, I could never fathom my parents as a couple; they fought constantly and seemed better off apart. So it didn’t matter that the very thought of them going to Henry’s End—of doing anything together—felt as foreign to me as a time with horse and buggies. What mattered was the food.

I can’t tell you exactly what we ordered on our first visit. But I’d put my money on the dish that would become my family’s signature: the raspberry duckling—crispy with a not-too-sweet glaze, skin that shimmered like lacquer, the meat soft and tender underneath. Every entrée was served with two sides: rice pilaf—perfectly fluffed and shrewdly spiced—and French green beans with the long ends left on. And for dessert? A flourless chocolate cake with a gooey molten center, topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

My dad’s plan worked. From that day on, every month or two, during our usual visits, my sister and I pleaded with him to take us back. And why not? He had moved out, after all—didn’t he owe us that much?

It didn’t take long for the restaurant staff to begin to recognize us: Mark, the clean-shaven owner; Denise, the ebullient hostess; and Albert, the hard-nosed busboy. Each time, they sat us at our usual table, my dad with his back flush against the exposed brick. We grabbed wantonly from the basket of fresh bread—dark crusty baguettes, thick slices of Irish soda bread, sesame seed breadsticks—served alongside a ramekin of whipped butter just soft enough to sink a knife tip into. We took sips from the selection of wines—fruity, bitter, sweet—that my dad held in slender glasses. We ordered a second dessert.

It was the place where, for the duration of a meal, we could pretend to be something we weren’t. My dad could be carefree, with more refined tastes and more discerning judgments—someone who could hold out a thin sliver of plastic at the end of a meal and have us play-guess at the bill, as though money could be spent that frivolously. At Henry’s End, we could all be made sophisticated—especially in the eyes of our dinner guests. Such as my dad’s new girlfriend, who would become his new wife and, later, our ex-stepmom. And the then-sophomore at NYU—only three years my senior—who my dad dated for a year before parting ways. And it was at Henry’s End that my sister and I, momentarily sated, could be, to any casual onlooker, the product of a two-parent home.

The illusion was powerful. In a city already dripping with refinement, dinner at Henry’s End felt like the height of civility. Where else could I relinquish the shy, maladjusted teenager I studied in the mirror and slip on a better version of myself? So by the time I had my first serious girlfriend, there was one place I knew I’d have to take her.

*

We had been dating for nearly a year when, in 2006, my college girlfriend Yitka flew to New York to visit me over summer break. I was nervous, naturally, and determined to show her the best that my hometown had to offer. A Kansas native, she could tolerate the city in small doses. I caught her as she glanced, wide-eyed, at the skyscrapers in the Financial District, the neon of Times Square. We sunbathed in Coney Island, counted the seahorses at the aquarium, picnicked with bagels in Central Park.

“You’re Sam’s son, aren’t you?” Denise said when we walked into Henry’s End for dinner, her dangly earrings twinkling. I nodded greedily, as if my dad’s patronage alone had granted me some degree of legitimacy. Cachet by association. As though Henry’s End was somewhere I belonged too.

Denise led us to our usual table—and I sat in my dad’s seat, my back cool against the exposed brick. I was wearing a striped button-down shirt one size too big, my white undershirt visible over the top button. Yitka and I were both playing at being adults. The set was carefully constructed: tea candles lit, a cloth napkin draped over our laps, the cutlery steely in our grip. Only we hadn’t memorized our lines. Time seemed to slow, then stop and, in lieu of conversation, we took turns reaching for the bread and butter, which was anchored between us like a buoy on uncertain seas.

It was the first time I had gone to Henry’s End without my dad, and I made myself crazy, convinced I wasn’t living up to the full experience. Would I really impress Yitka this way? What would my dad have done differently? I eyed the wine list hopelessly. I recommended the raspberry duck. Denise—bless her soul—brought us a second basket of bread. I had a crisp one-hundred-dollar bill in my pocket—a week’s worth of work-study savings—that I desperately hoped I wouldn’t have to spend all of. When the bill came, I had to stop myself from making Yitka guess to see who could get the number closest to the total.

I felt my dad’s presence looming over the meal like a specter. He had made it all— dating, romance— seem so easy. I thought about all the times we’d gone to Henry’s End together, but also the countless times he had gone on his own. How he’d courted my ex-stepmom there, their legs touching under the starched white tablecloth, and the other women he’d brought there since their divorce—women with whom he’d had trysts so short we’d never heard their names mentioned twice.

But what scared me most was wondering if I would suffer the same fate. Would there be others after Yitka? How many women would I end up bringing to Henry’s End over the course of my life? Striving, each time, to be the best version of myself. And hoping that each one would be the last person I would ever love.

*

My family’s history with the restaurant began even earlier than 1994. The very first person my dad accompanied to Henry’s End was not a date but his mom, a then-schoolteacher at Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn. My dad’s dad had long moved out of Brooklyn by then and never knew the place.

My dad’s parents, like mine, had been divorced for most of my dad’s life. I had assumed, at first, that it was that way for all families. When I was starting grade school, I accidentally broke my mom’s heart when I told her that, after I grew up and had kids of my own, I would prefer to see them every other weekend, just like my dad saw us. But later, after meeting the other kids in my neighborhood, I began to wonder whether divorce was instead unique to me—something genetic or contagious—a virulent strain that ran straight through the family blood line, inviolable and inescapable. As if it were only a matter of time before it would wend its way to me.

Seasons passed after that dinner with Yitka. In the summer months, my dad, Hannah, and I ordered softshell crab seared with butter and basil, the perfect balance of chew and crunch. In the fall, we made selections from the Wild Game Festival menu: wild boar ragu, buffalo short rib ravioli, elk chops served with purple fingerlings and red carrots that were as colorful as a box of crayons.

Inside, under the cool lights, Henry’s End remained the only constant in the shifting tides of our lives. By 2009, my dad was single again, and my sister was in the throes of her first serious relationship. And, long broken up from Yitka, I had graduated from college and moved to northern China, about as far away from New York as a person could get.

For the next three years, when I came back to New York for holidays, the visits were always brief. Still, when the three of us got together, we reprised the one family tradition that each of us cared enough to keep. Henry’s End was part of our family’s story, a forever reminder of home. It had watched us grow up, drift away, come back together, forming a collective consciousness greater than any other we’d shared. The decor and the menu had remained virtually untouched since 1973, when Henry’s End opened. No matter what else was going on in our lives, we could step into a past where everything remained unchanged.

Sometimes, Mark or Denise would ask us about our once-dinner dates, and we’d have to shake our heads. “Happens all the time,” Denise would say, waving a hand in the air. “You’re definitely better off without them.”

And we were. We raised our glasses and cheered. Who cared if we didn’t have anyone, as long as we had each other? It didn’t matter that all of our attempts at love seemed inevitably bound to fail. Relationships that would start somewhere and lose their way as time ran its course. A reminder that even the best things in life never last very long.

*

In 2015, ten years after I’d left New York, my sister took her boyfriend to Henry’s End for the first time. Hannah ordered the raspberry duck and, for dessert, she and John shared the chocolate cake. After dinner, when they turned down Henry Street and walked along the promenade looking out toward Manhattan, John dropped to one knee and asked her to marry him. Perhaps no one was more surprised than Hannah. They were married the following year, in a spring ceremony at a small brewery in Allentown, Pennsylvania. For the next two years, they celebrated every birthday dinner at Henry’s End—each alternating the fifty-percent-off-one-entrée coupon they received in the mail—until the summer they got divorced.

I’d avoided the place for years by then. This wasn’t entirely purposeful—neither my dad nor I lived in the city anymore, and the three of us rarely had a chance to see each other together. Besides, I’d learned from Hannah that there had been changes to the menu. The raspberry duck had been inexplicably replaced with strawberry. The warm chocolate cake had gotten the axe. And no longer could we ask for multiple tastings of wine. The era of abundance was over.

I’d come to believe that Henry’s End was cursed. The fact that Hannah’s marriage had its beginnings at the same place where so many of our other relationships also failed seemed like more than just a fluke. Were we, as Denise said, truly better off without those dinner dates? Or was there something else afoot?

*

I’m getting married this year. Even the sound of that sentence scares me. Added to all the normal anxieties about a wedding is the sinking feeling of hopelessness about a future beyond it. I haven’t had very many role models—family or otherwise—who could help me navigate this next step. What does it mean to devote oneself entirely to another person? To be accepting of each other’s proclivity to change? To remain loyal—indeed, to love someone— despite their faults?

My girlfriend, Meghan, and I have been dating for over five years. She’s been to New York and met my family dozens of times, but up until recently, I’d never taken her to Henry’s End. Since Yitka, I hadn’t taken a single girlfriend. Selfishly, I didn’t want to be remembered by the staff—by the restaurant—for trying hard at something and failing. I believed that a person only ever had a finite number of chances at falling in love, and that Henry’s End was a kind of love-affirming genie. I was already down to two wishes, and I didn’t want to dash my hopes on any relationship that didn’t seem like it would go the distance.

But the genie still nagged at me. Henry’s End had been the site of so many cherished memories. It had been a way for me to connect with my dad following my parents’ divorce and it had been the place that reminded me, after years away, of a home I could still come back to. But it had also witnessed some of the most painful events—breakups, disappointments, the shame of getting older. The truth was that the bad memories were blended in with the good, like a roux, impossible to parse apart. It was like a relationship in that way. When you distilled it down to its essence—stripped away the passion and regret and expectations—the only thing left was love.

*

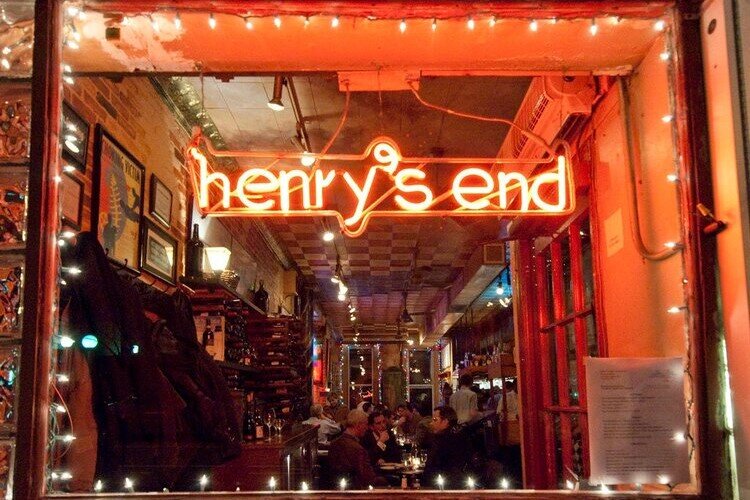

After all these years, it still thrills me to see the neighborhood. The towering Hotel St. George right outside the subway exit, the (now defunct) Brooklyn Heights Cinema with its Hollywood star carpet. Where else in New York can you find three consecutive streets named Pineapple, Orange, and Cranberry? Henry’s End is still located on Henry Street, but it’s moved one block south. After forty-six years, the building that housed it needed to undergo a major renovation earlier this year and they decided to move instead of shutting down indefinitely.

As I walked with Meghan from the Clark Street subway station, a nervous feeling rose in my chest, like it had when I first took Yitka around New York over a decade before. I felt the presence of every past version of me, layered one on top of the other like a palimpsest: the man treating his dad to dinner; the shy college kid trying to impress his girlfriend; the young boy, looking calmly around the table, surrounded by a sense of fullness.

The exterior had changed. Instead of the simple brick facade with the cut-away door, there was now an outdoor seating area with stiff blue umbrellas, glass decals in the window with bold white lettering. It was a reflection of the times, a New York I had long left behind. But still, there was the possibility for renewal, for new memories to steep with the old. Out front, a new generation of young parents sat at slate-topped tables alongside their small children. The same neon “Henry’s End” sign still glowed red in the front window and out into the night.

“Just the two of you this evening?” the young hostess asked. How long ago had Denise—had any of them—moved on? Part of me was devastated, realizing there would be no one left at Henry’s End who would remember us or our family’s legacy. But another part was relieved. Maybe the past didn’t have to define the future. This could be the start of a new chapter, free from any preconceptions.

I spotted an open table adjacent to the wall that in another lifetime the three of us might have called our own. The hostess nodded and placed two menus under her arm.

“This way,” she said. “Follow me.”

*

Originally published in Kitchen Work.