It was summertime and I was eleven. My mom lopped a porcelain bowl over my head and with the other hand, she quietly trimmed around the circumference of my skull until the sides of my hair looked roughly flush—a mushroom cloud billowing out of the top of my cranium. It never registered as out of the ordinary—some of the girls in my class were just hitting puberty and I had too many other things on my mind aside from whether or not my sideburns were even. Still, my mom insisted that I should have my hair cut professionally before I got to middle school. And so it was decided—we went to the now defunct Supercuts on West 8th Street in Manhattan and by the time the nail-biting, 20-minute ordeal was over, I was in tears.

To this day, I still can't pinpoint exactly what tipped me off, but the loss of my bangs cannot be overstated. What I saw that afternoon when I stared bleakly into my mom's cosmetics mirror on the 2nd floor of a K-Mart, was a side part, hair that fluffed up at the top, and was buzzed flat and prickly all the way up the back. In short, it was a hairstyle not too dissimilar from the way I have kept my hair in the twelve years since, and my mom has never once had to cut my hair again. My hair has been a defining part of my identity ever since, so I suppose if I ever track down that hairdresser, not only should I give him the tip I had walked out on, but I should also extend my hand and thank him as well.

But it wasn't just my first professional haircut that left me wanting. I daresay that in my whole life, I've never once had a haircut I was completely satisfied with in America. Usually, this would necessitate finding a new hairstylist, but it's been that way with a myriad of barbershops in all corners of the city. The general arc of a haircut for me goes something like this: reel from the misery of my first two weeks with a haircut that is too short, lavish the four weeks when my hair has grown out to the point where it looks presentable, and endure the next two weeks until I can finally bring myself to go back to the barber again with hair that is too long and unruly.

I have come to terms with this fact, accepting simply that my hair will look bad for a quarter of my life, but that it will inevitably go back to looking decently again for another half of it. This has afforded me the opportunity to take a lot of risks that others might be afraid would make or break their image. At Oberlin, I never paid for a haircut, and instead, depended on friends to cut my hair for little or no money, giving would-be barbers free reign to try almost anything. Most had at least had access to a hair trimmer, which was really the only criteria. As a result, I've ended up with lopsided fauxhawks, short-trim buzz-cuts, and straight-hair Afros, all in the name of fashion and frugality.

The impeccably-decorated interior of the "Gold Cut Modeling" hair salon located in the back of the campus bath-house.

My hair is a big part of my identity here in China too. It is black, which automatically sets off alarm bells in people's minds, prompting questions of whether or not it is my natural color, and then, if it is, how it is possible that such a thing could be. Additionally, one of the things my students always joke about is when I walk in to class at 8am on a Monday morning, my hair in kinks and cowlicks, and proceed to teach a lesson as usual. In China, hair styles change about as quickly as the weather—after a long winter vacation, it always shocks me to find about half of my class with their hair newly layered or permed, sprouting brown curls or blond highlights.

So, when it was inevitably time for my first haircut in China, I was understandably a bit nervous. If my haircuts always ended up so badly in America in spite of being able to speak the language, how could they possibly look good here? My first haircut came immediately following the shut-down of campus due to H1N1. As a result, the countless barbershops and hair salons that lined North Yard were temporarily closed down, so I relegated myself to the only place left. It was a small, brightly-lit salon located in the back of the campus-run bath house. In a country where any given establishment is either run down and dilapidated or incredibly gaudy, it took the latter role.

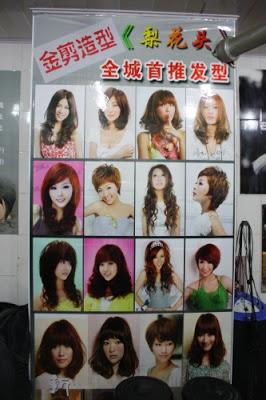

It has the kind of atmosphere you might expect. A row of neat leather-pleated barber stools line the front of the store opposite a long full-length mirror. Like most other barbershops, there is a speaker in the back blasting pop music as a way to drum up business and the walls are plastered with pin-ups of fawning young women sporting new hairdos. In the back sits a high chair with a stone basin for a headrest—here, it is standard practice for patrons to first have their hair shampooed and washed before getting cut. On my very first visit, I was accompanied by Anne who offered to help translate for me in case any difficulties arose. It felt like my mom at my first haircut, telling the hairdresser careful instructions that he would later go on to ignore.

I got a chance to meet the owner of the hair salon who, like most of the other employees, was simultaneously nervous and overjoyed at the prospect of cutting a foreigner's hair. When asked about the poster, he said he had personally cut the hair of each of the girls pictured.

In my experience since, I've probably had eight or nine haircuts at a handful of different barbershops on campus. Whereas before I was nervous about getting my hair cut, now I actually look forward to the slightly goofy conversations, always fixated on some detail of my life in America, and how much more I can understand each time I go. I always tell them the same thing about how to cut my hair: about the same shape as it is now, a little shorter on the sides, and you can use the electric cutting machine on the back. They wash and dry my hair twice, plus throw in the occasional shave, all for eight yuan, just over a dollar, and about twenty times cheaper than any haircut in the states. And miraculously, the haircuts I've gotten here have been among the best I've ever had.

I think it has a lot to do with them knowing intuitively how to cut “Asian hair.” Whereas Nick and James have occasionally gotten the short end of the stick and other foreigners opt not to get haircuts at all, I revel in the new-found realization that my hair doesn't have to look bad for a quarter of my life. It can look good mere minutes after walking out of the hair salon. On my last visit, I had just gotten out of a conversation about job opportunities in America after college, and was walking up to pay my tab. The owner looked at me and then looked at his watch. This is too much, he smiled, motioning me to take back some change. The mid-day price is only five.

*

This post too is of the “double feature” variety, totaling about 1200 words.